TOM FRANCIS

REGRETS THIS ALREADY

Hello! I'm Tom. I'm a game designer, writer, and programmer on Gunpoint, Heat Signature, and Tactical Breach Wizards. Here's some more info on all the games I've worked on, here are the videos I make on YouTube, and here are two short stories I wrote for the Machine of Death collections.

Theme

By me. Uses Adaptive Images by Matt Wilcox.

Search

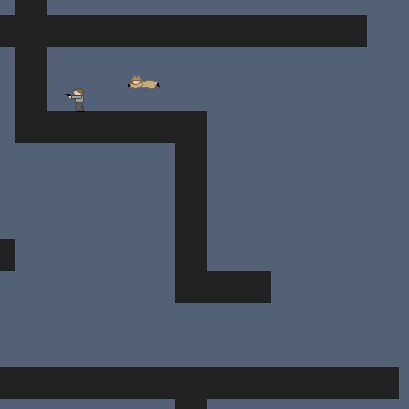

Ludum Dare Day 1, 8AM: World And Movement

I present to you, SnowBot! So called because the only things I have made for it so far are some snow and a robot.

It is the ugliest game ever made, but it works – the robot chases your cursor while you hold the mouse button, and decelerates when you release it.

Obviously with 48 hours to make something, you start to look at what really takes time, and the answer is invariably ‘tweaking’. So I made a pact with myself: no tweaking till the game is virtually done: of graphics, movement, controls, anything. I’m allowed to change things once or twice to get them functional, then they’re set in stone until the rest of the thing is in place.

I have two days, so my plan is to make the game in one. That way I can spend the second day making it good, or making up for how badly I failed to meet this ridiculous deadline on the first. My game is going to be crude and ugly no matter what, so I’m happy to make it even cruder and uglier to give myself some time to balance it and make it more fun.

In my head, this meant getting a character moving around the world in the morning, then making content in the afternoon. Turns out the first part only really took an hour, two with all the faffing with all the blogging and setting up screen captures for the time-lapse video I’m hoping to make of this process.

So next up is putting an enemy in the world, and letting the two shoot each other. Video games.

Ludum Dare Day 1, 6AM: Theme And Ideas

It’s 6am, it’s freezing cold, it’s pitch dark, England is caked in snow and the theme of Ludum Dare 19 is Discovery.

Discovery is what I was hoping for. I think one of the close runners up, Containment, would probably have led to a more interesting selection of games, but I had a clearer idea of what I’d do for Discovery. I knew if this one ended up being picked, I would have to make something involving randomised content. That’s what makes Spelunky so exciting to play, and that’s probably the greatest game about discovery I’ve ever played.

Unfortunately I’m not Derek Yu, and I only have 42 hours, and I’m wasting time writing a blog. So my game will be a little less ambitious.

To fit the theme, I feel like the pleasure of the game has to have something to do with the discovering. And the only thing gamers truly and instinctively care about is stuff that benefits them in the game. So not only does it have to be the content rather than just the scenery that is randomised, the unique elements of that content have to feed back into character progression in some way.

My plan currently is for something top down, where you direct your character – probably a robot – around a large landscape with the mouse, encountering enemies with randomised stats. Destroying them will let you salvage some of their traits, so a very tough enemy would boost your hitpoints when you destroy it.

Someone on the Ludum Dare site joked that everyone should not only have to stick to the chosen theme, but also combine it with Christmas. So if I can draw it in any meaningful way, I’ll set my game in the snow.

Ludum Dare 19

I’m going to enter Ludum Dare this weekend. It’s a competition where you have to make a game in 48 hours, based around a theme. Right now the theme voting is still going on, and will only be announced when the competition starts in four hours. I’m exhausted so I’ll be asleep by then, ready for an early start tomorrow.

I’ll be using Game Maker, Paint.net and an amazing program I only just discovered while reading the Ludum Dare rules: sfxr. It generates sound effects according to some sliders you set, and you only have to click the preset buttons a few times to realise this or something similar is where all Spelunky’s sounds must have come from.

When you enter Ludum Dare, you can decide to go for the competition, or the jam. In the compo, everything must be your own work and the theme is not optional. Those games are rated by participants in various categories. In the jam, you can work in teams, take an extra day over it, and the rules are pretty loose – you just won’t be judged.

Unless the theme is awful, I’ll be going for the competition. Right now it looks like the forerunners for theme are Discovery, Depth and Containment, which I like a little, not much, and a lot, respectively. I thought I’d be okay with any theme, but some of the finalists are stuff like “Text input action game”, “Game based on a year” and, no kidding, “Don’t die”. If it’s any of those, I will almost entirely ignore them and maybe just go in for the jam.

I’ll probably blog my progress, and try to do a time lapse video. I may end up with nothing – I’m not fast, experienced, or good at judging scope yet, and I plan to eat, sleep and take breaks. My God have mercy on my soul.

Gunpoint And The Other Game

I had an idea for another game, recently. It’s an RTS that would solve a lot of my main frustrations with RTSs, with a few fairly simple mechanics. And it’s an idea that keeps spawning other, smaller ideas, and suggesting parts of itself I might like to cut out to make it even simpler and better.

It’s gamey in a way that Gunpoint isn’t, in that it’s really just a few basic systems: no context, story or even content would be necessary for it to work on a basic level. And it might actually appeal to people outside of my skull, in a way that Gunpoint probably won’t. No logic or thought went into my choice of a jumpy platformer about a private detective for my first game, it was just the first idea that interested me. The RTS feels like something worth making, and something that someone else will probably make if I don’t.

In other words, everything’s been telling me to just stop making Gunpoint, learn Unity, and switch to this newer, better, more potentially successful idea.

I’m not going to. Abandoning an old idea doesn’t solve the problem of forever having newer, better ideas. They’re always going to come faster than you can make them, and for a while, they’re always going to make your old ones seem less exciting. Whatever you do in response to that is what you’re always going to do, so if I ditch Gunpoint to make this RTS, I’d ditch the RTS to make the RPG idea I’m inevitably going to have in six week’s time.

But going back to Gunpoint is harder now. Not because it’s an unexciting idea – the thing at the heart of Gunpoint, which I haven’t really talked about yet, still gets me totally fired up. But looking at it after this gleamingly simple, efficient new idea, it looked incredibly flabby, unfocused, and most of all daunting. I just don’t know how I’m going to do half this stuff, and some of it doesn’t seem very connected to what I’ve done so far.

I’ve tried to simplify Gunpoint lots of times, but I’ve never really questioned that it was going to be story-driven. It couldn’t just be missions, it had to be punctuated with scripted sequences, major characters and predetermined developments.

But that wasn’t really a design choice. I just automatically included it because I’d already written a bunch of scenes, dialogue and characters to flesh out the world in my head. It’s instinctive to write that kind of stuff when you’re thinking up a new world, and useful too. But I should have taken an extra step back and thought, “OK, why do I need to tell these stories to the player? And how much work is it going to be?”

I don’t have any new screenshots to show you. Here are some horses.

I don’t have any new screenshots to show you. Here are some horses.Now that I take a more squinty-eyed look at the roadmap ahead, I start to see just how much coding each one of these things is, and how little it adds to the game as a game. Making non-interactive scenes on top of your interactive ones is like making a second game – a shitty game no-one can play. And I know from editing GTA IV movies that I’m an obsessively redactive director: I’d never quite be happy with the way they played out.

So I’m scrapping all the non-interactive stuff. There’ll still be story context for each mission, but it’ll be the text of the briefing you choose from some kind of job listings site, and text message conversations with the client.

Oddly, since restricting myself to this for practical reasons, I’ve found it also makes more story sense: you’re a private agent specialising in illegal activities, so you probably would get your jobs from an anonymous site rather than walk-in clients, and communicate by text rather than in person.

It was an easy choice to make – I don’t have to delete anything, because the stuff I’m scrapping is stuff I haven’t made yet. I probably would have given up on a lot of it when I did come to build it. But what the other game has helped me do is clear it out now, while I’m working on the cool stuff. I had to make Gunpoint a more appealing thing to work on, and that meant cutting reams of big wibbly translucent flab until I could see the route to completing it. It clears the head, brings the game into focus, and makes it feel achievable.

Shrug.

Shrug.I’m always asking developers what they’ve learned from previous games, and sometimes they draw a blank. So I might start ending my Gunpoint diaries with a summary of what I’ve finally figured out.

Writers shouldn’t write games. Designers should give them a little box to write in, and they should write in that. I left my writer hat on way too long after coming up with a vague idea for the world of Gunpoint, and started writing the actual game. “This happens, then this happens, then you get this item-” Shut up! Games aren’t just first person movies, Tom. Design a thing that is fun, then write whatever story context that design needs.

‘Hard to do’ and ‘easy to do’ are irrelevant, ‘good value’ and ‘bad value’ are what matters. I say the story stuff was going to be hard to implement – it wouldn’t be, really. Not as hard as the central mechanic I’ve yet to start on. The difference is, if the central mechanic works, it’ll lead to dozens or even hundreds of fun interactions for each player. The story stuff would be fun a maximum of one time per player, likely not even that. It’s phenomenally bad value. If you’re Valve, and there’s some reason you really want to push this stuff, you can afford that. But if you’re one guy with no experience making games, you can’t.

Unrelatedly: Machine of Death day is in about eight hours. I’ve put together a post about how you can get it, what the postage will cost, and what other forms it’s going to be available in. That’ll go up once it’s officially MOD-Day.

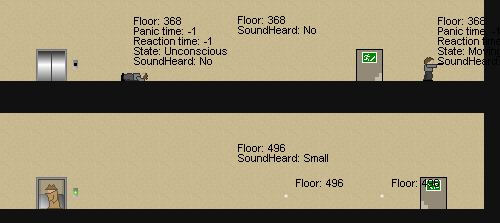

Gunpoint: AI

On some level, my game is going to be about fucking with people. When you get down to it, the reason I like Deus Ex isn’t because I have the choice of using a multitool or shooting a guy. It’s that I can trick the guy into doing what I want. If I don’t have the key to a door with a guard on the other side, I can just shoot a wall, and he’ll unlock it for me when he comes to investigate the noise.

People coming to investigate, in fact, seems to be the core rule in the most enjoyable deceptive play – whether it’s in Deus Ex, Thief or Hitman. So that was my one requirement for Gunpoint AI: you must be able to knowingly misdirect the AI. The fact that investigating suspicious noises is also semi convincing, semi effective behaviour for a guard is just a nice bonus.

I had a feeling this would be hard, and I knew it was probably a little too involved for a first project. But I was looking forward to trying, because AI is one of those nice juicy problems that’s too big to tackle. You have to break it down, and breaking things down in ways that make sense is one of my favourite things to do. I took philosophy and maths at university, so it’s about the only common thread in my voluntary education.

I wanted guards in office blocks to head to the source of suspicious noises, like gunshots or glass breaking, even if they weren’t on the same floor. It sounds dangerously like pathfinding, a famously sticky area, but I didn’t think it would come to anything like that. I can just break it down into a) how do I get to somewhere on my floor? and b) am I going to the sound itself or the stairs?

What I’m learning, increasingly, is that conceptual stuff is not the hard bit. Every high-level idea you have for how to translate a design concept into chunks of algorithmic code will probably work, and in fact is pretty easy to write. The hard part is a part I didn’t even realise was a part: order.

“I wanted guards in office blocks to head to the source of suspicious noises” – really? Did I want dead guards to respond to suspicious noises? Did I want guards to walk right past the player himself on his way back from breaking a window, in order to investigate the breaking of the window? Did I want guards who are being blown out of a window by the force of an explosion to stop, mid-air, and tell the others: “Oh hey, I’m closest to that broken window I was just flung through, I’ll go check out what caused it”? Did I want the guard who just shot you to run to your dead body and try to solve your murder?

Actually I kind of do, but that’s probably another game.

It’s easy to code what you want. But you don’t really know what you want until you’ve tried to explain it to a very, very stupid person. That was Socrates’ thing, in fact: he acted like an idiot to make people explain themselves to him on the most basic level, which usually revealed they didn’t truly understand their own beliefs. These days we have silicon hyperidiots to explain things to. They’re able to be much more stupid, many more times a second, than Socrates ever was. Coding is the Socratic method as an extreme sport.

Because the concept behind my AI system was simple, scripting it was getting increasingly complex. Every time I said something like, “Set this guard’s state to ‘alert’,” I had to first check that he wasn’t dead, or stuck, or in a lift, or being punched. And it wasn’t going to get any less fiddly: every time I added a new situation, I’d had to go back and add new exceptions to every line of code it could influence.

The only way I could make it simpler to code was to make it more complex to think about. It turns out that the nitty gritty of how an idea works in practice is a much more unwieldy beast than the high concept of what you want it to achieve, and it’s the former you really need to simplify.

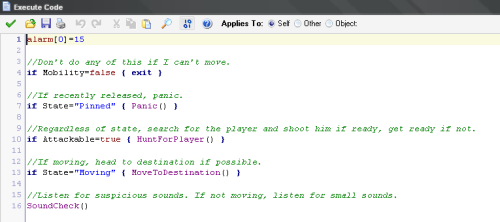

So now I have an intricate system of connected timers, tracking five or so independent properties of the AI’s mental and physical state, and it’s a mess to think about. But in code, it’s remarkably straightforward. I’ve turned every sub-problem into a separate function with a human-readable name, replacing stuff like:

if ((sprite_index=sGunman && oPlayer.x > x) or (sprite_index=sGunmanLeft && x > oPlayer.x))

With: if HesInFrontOfUs

The top level code is now just this – the pink things are functions I’ve written that call in other chunks of code:

And after a lot of tinkering, and a few maddening variable-definition errors I never really got to the bottom of, it actually works. You can lure guards from their posts, hide the other side of the stairs and jump them when they come out. Or you can make a noise on one floor, then travel to another while the guard there runs to the one you just left. It’ll get more interesting once you have more of a toolset: right now all you can do in Gunpoint is jump on people and whale on them. But it’s already actual fun to screw with the AI, so I’m pretty excited about what I can do with it from here.

By the way, Spelunky creator Derek Yu put up a great guide about what stops people finishing games, and how to avoid it. Since he inspired me to start this, it’s nice of him to also inspire me to try and finish it.

Lastly, I need opinions: man-sized air vents are a cliche. But are they an annoying one, or just a tool that ultimately makes a game more fun? In some ways they’d fit with Gunpoint’s movement system, since they wouldn’t have to be floor-level for you to get to them. But I don’t know how sigh-worthy people find them these days.

My ‘Enemies As Weapons’ Game Idea

The winners of the 48-hour game-making competition Ludum Dare were just announced. It’s a regular thing that awesome indie devs pile onto partly as a test of their skills, partly as a thought experiment, and partly just to jam and share ideas. The theme this time was Enemies as Weapons.

I didn’t enter, though lots of absolute beginners do, and it’s the sort of thing I love. But while I now feel capable of starting a small project like that, I don’t feel capable of finishing one in any kind of time. I was also pretty goddamn determined to get elevators working in Gunpoint by Monday, because four days on that is just kind of sad.

But I did have an idea for one. I think I like the competition’s theme because it’s suggests changing the state of enemies in a more interesting way than from alive to dead. Either to make them accidentally destroy things you want destroyed, as in games where you shove them into something or dodge their attacks, or to turn them to your side.

My game would be called Defect and Serve, and it’d be about bent cops. You’re a criminal who’s just been caught, unarmed, during an elaborate bank job. The arresting officer hints that he’d let you go for a hundred grand, and while he’d like to just take it from you, if you’re dead or caught there’ll be no explanation for the missing money.

Your only option is to pay up – tossing the money to him in bundles of $50,000 by clicking. Above his head is a meter labelled “Principles:” followed by two blue pips, and each bundle of cash makes one of them explode in a little shower of bills. When they’re both gone, he leaves and heads for the opposite end of the building.

It’s from a top-down view, and once that cop leaves you’re free to figure out a route to the exit avoiding the other roaming police. Each has a number of Principles pips, usually between 1 and 10. It’s possible to get out without running into anyone else, but if you do, you’re rooted to the spot and must chuck them a $50k bundle for each pip of Principles they have before you can go.

Once you’re out, the next levels are a series of heists where you start with limited funds, and make your way to vaults and safes to get more. Your objective is to steal more money than you spend bribing, obviously, so you avoid the very Principled cops like the plague.

A few levels in, you’re told you can also toss some extra cash to a cop after you’ve already turned him. This creates a red Loyalty pip, and if you give him as much Loyalty as he had Principles, you can order him to radio an all clear to the rest of the cops, making your current location safe for a while.

If you can double a cop’s Principles in Loyalty pips, you can actually click on another cop to order him killed. The turned cop will head for him, but won’t strike until the two of them are on their own. It’s up to you whether to distract or bribe the other guards to help him achieve that, or get on with sneaking through the building and hope he has the chance at some point.

Eventually you will encounter the odd White Knight cop, who’s impervious to bribes. If he’s guarding your objective, your only option is to have him killed. At this point cops with low principles become essential tools rather than minor threats, and you’ll actively try and run into one on his own so you can turn him to your side. Once you have, it’s worth intentionally alerting the White Knight to lure him away from colleagues, giving your turncoats the chance to take him out without getting caught.

I’m actually enjoying sticking with Gunpoint, it’s just impossible to resist coming up with a concept for a theme like that. I’ll probably have another Gunpoint progress report soon – I’m close to another milestone involving the AI, and I’ll be in a good position to figure out what kind of challenges are going to be fun in this frame work.

Even as it rapidly approaches an actual game, it seems to be getting further and further from the story-heavy finished article I had in mind when I started. I pictured it story-heavy because writing is trivial, but I’m starting to realise scripting is not. And it’s a low value type of work, only really good for one play through, and little to do with the medium’s strengths. I’m starting to wonder if there’s another type of content I can use to link a bunch of puzzles, or a more efficient way to convey story without visually depicting a lot of non-interactive events.

roBurky’s game, I think untitled, lets you convert enemies to your side or blow them up in a chain reaction.

roBurky’s game, I think untitled, lets you convert enemies to your side or blow them up in a chain reaction. Alien Abduction of Aliens, a simple grab-and-throw game that’s beautifully drawn, and even more beautifully named.

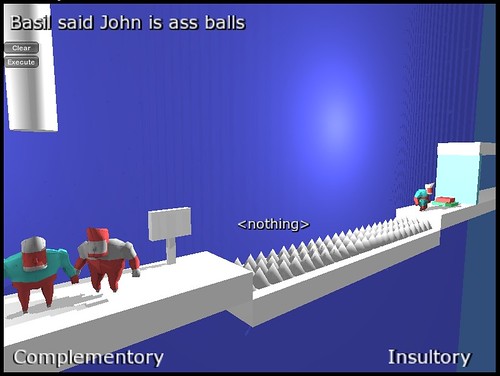

Alien Abduction of Aliens, a simple grab-and-throw game that’s beautifully drawn, and even more beautifully named. Sophie Houlden’s excellent Fib, in which saying “Basil said John is ass balls” is a valid puzzle solution. You lie to people to trick them into killing themselves, so that you can safely walk on their corpses.

Sophie Houlden’s excellent Fib, in which saying “Basil said John is ass balls” is a valid puzzle solution. You lie to people to trick them into killing themselves, so that you can safely walk on their corpses. The end game of the competition’s winner, Fail Deadly. It’s a smart and immediately fun subversion of an RTS where you build both side’s bases in an attempt to keep them evenly matched long enough for nuclear war to break out, killing everyone.

The end game of the competition’s winner, Fail Deadly. It’s a smart and immediately fun subversion of an RTS where you build both side’s bases in an attempt to keep them evenly matched long enough for nuclear war to break out, killing everyone.

Gunpoint: Making The Jump

I had a chance to work on my game in my week off, the one I was going to call Private Dick. That name is increasingly pissing me off, so I’m calling it Gunpoint for now. How relevant that title becomes will depend a bit on how much fun it really is to be at gunpoint, or have other people there, and what kind of options I can reasonably code for those situations. Currently everyone with a gun shoots you in the face the instant they see you, and there’s a certain comforting reliability in that.

I’m almost at Milestone 2 – they’re really yard stones, these things, because I can’t have spent much more than ten hours on this thing since Milestone 1. Here’s the plan:

Milestone 1: movement fully working, however horrible it looks and shitty it feels.

Milestone 2: one hostile who shoots on sight, and can be pounced on and beaten unconscious.

Milestone 3: two devices that are interactible. I’ll talk about devices once I’ve got them working.

Milestone 4: one fully working level that’s fun.

Milestone 5: a dialogue system why not?

Milestone 6: narrative reduces grown men to hopeless fits of sobbing.

Milestone 7: the Citizen Kane of games.

So I’m not really thinking clearly more than two or three milestones ahead – my plans change too much with each one for that to be worthwhile, and anyway it’s kind of daunting.

About ten of the people who signed up to test my game played Milestone 1 and told me what they thought of it. This was awesome. Not least because most thought it was a lot less horrible-looking and shitty-feeling than I was expecting.

It’s also a really exciting and eye-opening thing to have people interact with something you created, and have reactions you didn’t expect. People overwhelmingly wanted a certain move added that I’d intentionally left out. And they were right: I’ve added it now and it profoundly improves the feel of the game.

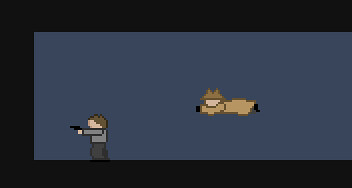

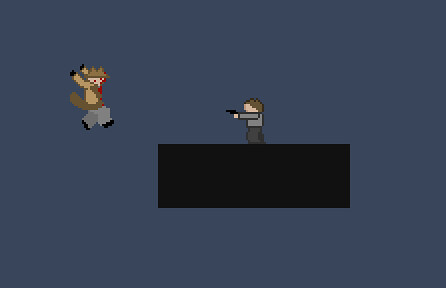

That milestone was all about the jump: the tiny freelance agent you play can leap preposterous distances in any direction, and cling to anything he hits. This milestone, number 2, is about using that jump to pounce on angry gunmen while they’re not looking, then punching them in the face while you have them pinned to the ground.

That part took minutes, really, and is immediately and profoundly enjoyable. I hadn’t really thought about it before I coded it, but there’s no reason to force the player to let the gunman go after he’s hit him in the face once. I just made the mouse click smack him in the face, then return to the about-to-smack-him-in-the-face pose. You can jump off if you like, but in a survey of playtesters called me, 100% felt the need to beat him again and again and again, sometimes tapping out semi-musical rhythms with their facebeatings.

What was trickier was making the jump good enough that you could bet your life on it. One of the biggest complaints from the first test, even without any threats, was that people had trouble judging where their jump would go. I hadn’t even put a charge-meter in, and the strength of your jump increased quadratically as you held the button. A player’s instinctive grasp of basic movement mechanics doesn’t necessarily model quadratics effectively.

This was not a surprise. I knew what I wanted, ideally: a visual projection of the exact arc your jump will take. But like most of my plans, I had a few much easier back ups that wouldn’t work as well. Any kind of charge meter, I thought, would probably do.

The reason I’ve only spent ten hours working on this since the last milestone 5 weeks ago is not actually free time. It’s guts. Doing everything yourself is sometimes daunting.

The fun stuff: design, requires some less fun and harder stuff: coding. And the still quite fun stuff: coding, requires some much less fun, much harder and miserably unsatisfying stuff: art. When I’m not working on my game, it’s because I’m exhausted or distracted or just not in the mood to take on something that may, at any time, kick my ass.

What I’ve learnt from the whole process is this: guts. I’m not accustomed to putting time and effort into something and having it turn out shit, but I’ve found that when I actually get down and do it, it doesn’t take that much time and effort and not everyone thinks it’s shit. Just do it. Accept that not everything you do is going to be met with a steady stream of praise, venture outside your comfort zone and grow up.

That’s true enough for art, but it’s particularly true for coding. Predicting the arc of a player’s jump meant simulating the engine’s own internal vector analysis precisely, so that I could do all the calculations involved with it in a single frame. In other words, the game would have to play the jump out in its head thirty times a second, exactly the same way it would happen at normal speed. It seemed like it would involve an awful lot of trigonometry, which is tricky to code and tricky to compute. Having the game do it thirty times a second seemed like it would destroy performance.

Long story short, it was easy. If you’re smart about it, no sines, cosines or tangents are needed, just basic multiplications. It’s high school mathematics to model a rigid body under acceleration and derive a generalised formula for its position. And once you’ve got that, you just plug increasing values of time into it and create a dot at that position until you hit something. There are ways to make it more precise and reliable, but it already works so well that it’s completely changed the way I play.

I still don’t have a charge meter – I changed the system so that if you want to go further, you just click further away. It means you can make small, precise jumps without time pressure, and great long arcing ones without delay. And it feels great to leap six stories, through a window, and into the back of someone’s head. Then punch them to the beat of Seven Nation Army.

I whined a while ago about wanting to get to the point where the question is “Is this fun?” rather than “Why doesn’t this fucking, fucking work?” I’m there now, and from here until I’m done with the game or give up on it, there’ll always be “Is this fun?” questions to answer. There’ll still be many more things that don’t fucking, fucking work, but I’m tantalisingly close to having most of the building blocks to make real levels out of. Once I’m there, it gets really interesting.

Edit: just as I finish this, Sophie Houlden posts the text of her talk at World of Love, and it’s basically telling me to realise what I just realised.

Edit 2: Once I’ve tweaked it a bit, I could use some more testers to help me figure out if this iteration is fun yet. Any more volunteers? Mail me if so.

Edit 3: Now with animated gif.

Art Failure

I put it off for as long as I could, but after a quick prototype for Solo Trenchcoat Triathalon proved inconclusive, I had to put a second character in my game. This meant picking an art style, which was a problem for two reasons. For one, games aren’t art, and I know from contacts in the industry that professional game artists devote a good few hours of every working day to wrestling with this contradiction. And for another, the only acceptable sprite I’d drawn so far – protagonist Mr Conway – has his proportions and body shape completely concealed by an oversized, nebulous trenchcoat.

I am not an art guy. I feel visually dyslexic when I try to draw: I know the right shape when I see it, but I can’t visualise which pixel I need to change to make this deformed mess become that – even when it really is just one pixel. So I really struggle to depict what’s supposed to be going on under that trenchcoat. I have drawn Conway’s head big, monstrously big, a hangover from when he was to be a horrible space robot ineptly disguised as a human. Are his limbs similarly bloated? Can I really draw a head of that size without disguising it beneath a stylish hat? Can I balance a head of that size on a human body? Can I just set my game in a world where it’s considered indecent not to wear a trenchcoat?

All these things are problems because they resulted in this:

An armless, morose John Hodgman who just looks fat, awkward and wrong. Despite general murmurings of support on Twitter for the idea of a nightmarish Being John Hodgman world, I could see this wasn’t going to get good any time soon, so went in a completely different direction:

This would be a complete rethink, requiring a new treatment of the main character (not this douche), and a much more realistically-proportioned look. It might seem like more work, but stuff like this can be done pretty easily from photo reference. In fact, the fewer pixels you have to work with, the more artistry it takes to evoke something with them.

The trouble was Conway. Just as it was hard to extract a convincing human from the murky depths of his coat, it was almost impossible to drape the murky depths of his coat on a convincing human. Several takes ended up looking like Rincewind. And losing the outlines seemed to make every camel hue I picked for him look more and more like some kind of awful beige velour. I got as far as this before declaring it hopeless:

Doing a realistic-shaped guy from photo reference confirmed something I never realised about game art before I tried to butcher some myself: proportions, shape, size, colour, detail and expression are almost completely irrelevant. The thing that defines the feel of a character is pose. That’s why I haven’t been able to get rid of that lame original Conway sprite: everything about it is feeble and misjudged except the fact that he has his hands in his pockets.

Even that was a mistake: I just hadn’t got round to drawing his hands yet. But as soon as I saw it that way, it looked like the character I had in mind. Hodgman failed not because he looked like Hodgman – Hodgman is great – but because he was standing like a mannequin. I eventually solved my art style problem by realising art style doesn’t matter: the most basic possible shape would work fine so long as I could pose the limbs. So I just copy and pasted the original Conway, trimmed him a bit, and I had his first friend:

The relationship lasted as long as it took me to remember that the first character is meant to be an incensed gunman trying to kill you.

One or two people have very kindly offered to lend me their artistic talents. This is appreciated and noted, because if this gets anywhere I will almost certainly ask someone who knows what they’re doing to pretty it up. The reason I’m putting some effort into coming up with the basics myself is not because I expect them to endure, but because I need to decide on a tone. If I’d stuck with those slender realistic characters, the ludicrous super-jumping I’ve got right now might have needed rethinking. Now I know the game is allowed to be a little more cartoony, clean and simple.

Obviously now that there’s more than one person in the game, I’m thinking more specifically about combat. All my ideas for stuff like this have different modules: there’s a basic version I’m definitely going to try, then progressively fancier systems I could stack on top of it if it turns out to be interesting and fun.

That goes for the game itself, too: level 1 doesn’t need a combat system, level 2 doesn’t need a hacking system, level 3 doesn’t need a dialogue system, and none of the adapting plot stuff is relevant till after that. If one thing turns out to be cool enough to focus the game on, I’ll scrap whatever I haven’t made yet. That’s why I’m not worrying too much about the warnings about biting off more than I can chew: I haven’t bitten anything off yet, I’m just scoping it out.

The last thing I did was code the new guy to shoot you dead on sight, and already I’m liking him.

Collision

I’m only making a very basic game, and with a program that provides the base engine for you. But even so, that means hand-coding some pretty fundamental stuff, and it’s taught me that you can’t use the word ‘basic’ to describe anything you haven’t tried to code yet. I like to do stuff like The Hardest Logic Puzzle Ever in my spare time with a Google Docs spreadsheet (and xkcd’s The Hardest Logic Puzzle In The World in a text doc), but implimenting the most basic laws of game worlds is on a whole other level of complexity.

This bit of game logic, for instance:

Is impossible. I don’t mean hard, it’s just not the way algorithms work. You have to pretend it is, though, and the intricacies of that are what’s taken up most of my time.

The issue is that time progresses in discrete chunks in games, so just the word ‘when’ is problematic. Real life doesn’t really care if it’s not at exactly 1 second or 2 seconds that a man walks into a door, he just stops when he hits it. Code isn’t smooth, it has to re-examine and re-create the whole world sixty times a second, and there’s nothing in between these frames. Unless you want everything to move very slowly, some things are going to have to move more than one pixel at a time. That permits a nasty possibility: after 1 frame you haven’t hit anything, and after 2 you’ve already gone through it.

So collision logic fudges it one of two ways: the game either waits until you’ve already gone through something and pops you back out, or it looks ahead to see if you’re going to hit something and pretends you already have. The effect can be seemingly perfect, since these precautions are computed before the result is drawn on-screen, but it makes the underlying logic fiddlier than it ought to be.

Generally, though, it’s all fine so long as your character is a solid unchanging block.

Old-school platformer protagonists versus actual human proportions. Chick proportions not pictured.

Old-school platformer protagonists versus actual human proportions. Chick proportions not pictured.That’s why a lot of 2D games have very compact, boxy characters: the game can treat them as a simple rectangle regardless of what animation they’re playing. Real people change shape much more dramatically when they run, jump and hit things. If you want a human-like character to dive headfirst into a wall – and I do! – you have to solve this insoluable problem for a thing that keeps instantaneously and dramatically changing size and shape.

I won’t get into why this is even more complicated, difficult and annoying than it sounds, but suffice it to say that the next time I fall through the ground in the latest FPS and plummet into the infinite grey limbo below, I won’t be thinking “Why can’t these idiots fix shit like this?”

I will be thinking “Why don’t these idiots account for shit like this?” though, because it only took me a few days of tinkering to realise a fundamental law of coding.

Then code what to do when it happens.

So early on, when I had so many collision bugs to fix that it seemed daunting, I spent some time on an “Oh fuck, I’m stuck” subroutine. It’s a little spiralling algorithm that searches with increasing desperation for a nearby space to teleport you to, should you somehow get stuck in solid matter. I know I’ll never solve all the minor or rare collision glitches that could happen, so I feel I should at least try to make sure they don’t break the game when they do.

Getting collision logic stable and robust was the hardest thing I’ve had to do so far, and the most intricate stuff I have planned for the game now seems trivial by comparison. I’m looking forward to the point when I’ve done enough of the coding that the question becomes “Is this fun?” rather than “Why doesn’t this fucking, fucking, fucking work?”

Private Dick

I’m making a game! I will probably never finish it! But I thought I’d start talking about it anyway, to keep my goals straight and get feedback on my ideas as I go.

I’m doing it because Spelunky, one of my favourite games ever, was made by one guy in a program called Game Maker. Obviously it doesn’t follow that “If design/coding/art genius Derek Yu can do it, I can too!” But it does make you realise that game-making programs aren’t just for shitty test games. Since that was pretty much my last remaining excuse for not doing this thing I’ve had a constant urge to do most of my adult life, I started doing it.

My game is about a little dude in a trenchcoat who sorts out – or completely screws up – delicate problems like hostage situations, with a few pseudo-science special abilities. He’s sort of a drunk, asshole Inspector Gadget – hence the working title, Private Dick.

I wanted to see if, with little time, less talent and no experience, I could make a game that would achieve some of the things I’ve always wanted from the games I play. I want a game where:

A gun going off is a big deal. Existing games tend to be divided into ones where guns go off constantly, and ones where guns don’t exist. The latter don’t have enough guns for my tastes, and in the former guns become meaningless. You shot a man in Reno? I shot 384 men 7 times each in Vegas, and I still didn’t complete that game. The reason guns are an exciting element in a thriller is that they can enact sudden, massive, shocking, permanent change. I want to see them play that role in a game.

Failure isn’t terminal. In most games, you do what you’re supposed to or you die and retry. Even if you don’t physically die, failure means a restart. I want a game where life goes on if you fail the mission, and most of the ways you can fail don’t kill you. The story adapts to the outcome of your missions, and death is a rare, shocking, worst-case scenario. I don’t want anyone to have to repeat anything unless it makes no sense to continue. Edit: More on this in the comments.

You can change things in non-destructive ways. You can change them in destructive ones too, but that comes as standard in gaming. I don’t know if I can make anything you could meaningfully call emergent with my resources, but I want to make a game whose levels you can tinker with, reconfigure to your liking, and see those reconfigurations interact with each other – not just with you.

Movement is superhuman, but constrained by physics. I need it to be superhuman because I want getting around to be quick and satisfying, but I want it to be physically coherent. Most games don’t do this: almost all platformers let you move your guy around while he’s in the air, by some unexplained force. I’m not going to do anything fancy with physics in my game, and it’s not going to be primarily about movement the way platformers are, but I want the movement to make physical sense. Anything that doesn’t isn’t convincing to me, and that hurts a game’s feel.

It’s this last thing I’ve been working on so far, a few evenings a week. I’ve nearly got it FYS – Functional, Yet Shit. This is my standard for implimenting a mechanic before moving on – there’s no sense fine tuning or fully animating until I know how it fits in with everything else. Getting movement to that point will put me about 10% of the way to a playable level that includes all the main elements I want in this game. I’ll be surprised if it takes less than six months, sad if it takes more than a year, and amazed if I stick with it that long.

Writing about it here is one way I’m trying to improve its chances of reaching a playable stage. Explaining it to someone else forces me to keep my thinking clear, explaining it to you guys might be a good way to get feedback, and explaining it publicly makes giving up all the more embarrassing. So far I haven’t told you much, but if you’ve ever worked on a game I’d love to hear any general advice.

I’m already ignoring the golden rule: focus on one thing and do it well. I don’t know what I can do well yet, or what’s worth doing well, so I’m roughing out everything that might work and I’ll focus from there.

My plan is to talk more about what I’ve done so far than my future plans, so I’ll write about movement once it’s FYS.

Making Nuclear War More Interesting In SupCom 2

The notable thing about Supreme Commander was that it let you march a thousand robots around a 640,000 sq km battlefield – more like a county, actually. Supreme Commander 2 doesn’t let you do that, so the initial reaction is ‘Oh.’ But it’s still leagues ahead of every comparable strategy game in scale, control, and stompiness of robots.

The upside of all the scalebacks is primarily speed. It doesn’t really matter whether you pay for the stuff you build gradually (SupCom) or upfront (SupCom2). SupCom2 cuts out the interminable upgrading process to spectacularly accelerate how quickly you can build something vast, gleaming and capable of a war crime. It’s a less remarkable game, but a much more playable one. And even though its matches unfold eight times faster, I’ve already sunk more hours into it than the first.

A few things stop it from completely replacing the first game, most prominently the scale. A few things stop it from being the perfect evolution of the real-time strategy; a few signs of timidity in the Research options. And a few things stop me from really wanting to play it online with strangers – it appeals more than any other RTS in that way, but I still have to customise it a little to be happy with the playing field. So I wrote a few posts about how to fix all these things.

Some of the basic stuff probably isn’t controversial: it needs more eight player maps, two or three ten player ones, more sea maps, and more sea in the sea maps. AI that doesn’t build more transports than it can fill, and a ‘Very Hard’ AI that builds Experimentals with near-perfect efficiency. And a visible build queue, so that things don’t have to be paid for until they start construction, you can see what’s going to drain your resources, tasks can be reordered, and repeat-building factories can start churning out units again when nothing else is sapping your resources.

The Research tree of upgrades you can unlock is a wonderful improvement over the usual nonsense, but they’ve needlessly lost that concept of truly elite units. Experimentals are a different kind of “Fuck you” to the classic “Fuck you, one of my tanks can kill ten of yours.”

Upgrades should be more specific, more significant and more visible. The five incremental ‘Training’ upgrades should be cut to two very expensive ones that each double the units’ effectiveness, and make them physically bigger. It has to be immediately obvious “Shit, that’s an upgraded tank” or “Holy shit, that’s a maxed-out tank”. It should also be different for each race: UEF’s should upgrade health more than damage, Cybran damage more than health, Illuminate damage, health and range.

And scrap all generic ‘damage’, ‘health’ or ‘rate of fire’ upgrades – that’s what Training’s for. They should be replaced by unit-specific upgrades that change their form, size and function more dramatically. So instead of “+30% damage to all turrets” you’d have “Anti-air turrets upgraded to surface-to-air missile launchers, increasing their range and damage and letting them lock on to fast aircraft.”

Every upgrade needs to make a visual difference that’s obvious from any zoom level where you can see the model. Training increases size, a new weapon type changes the shape of the unit and adds an effect, regen causes them to spark colourfully when healing, etc.

This has been a huge problem for me in both games. Because it’s nuclear war, but it’s boring. Either side can build a nuclear missile, but either side can also build an anti-nuclear missile for half the price. The only reason not to is that half the price of a nuke is still significant. So an actual nuclear war is just a contest of who can be bothered to click their button the most, and since the defender has an economic advantage, it’s almost always him. The only time nukes actually get used is when your opponent is too new, stupid or artificial to know to build anti-nukes. Top marks for matching reality, zero marks for fun.

The only good moments we’ve had with them have been when, in co-op, a stupid AI has built their only nuke defense on the fringe of their base. One player readies a nuke, the others send in a combined strike team to take out the defense silo, and the moment they’re successful, you launch. Awesome. But in normal play, a strike force capable of taking down a massively tough nuke defense silo in the middle of the enemy base is also a strike force capable of taking down the base itself. Here’s my proposal:

All factions should be able to build a basic Nuke Defense silo without having to research or unlock it. It has unlimited anti-nukes, but it can only fire one at a time, and they don’t neutralise the nuke: they detonate it. So to avoid just blowing yourself up in a slightly different way, you have to build it well outside your base, and defend it with stuff you can afford to lose or move. The silo itself is nuke-proof – it’s basically a bunker – so you don’t have to rebuild it each time.

The idea is to turn nuclear war into a fight, rather than who can be bothered to click more times. It’s easy to defend against nukes, but only if you can defend a forward position in regular combat. Accordingly, it’s harder to nuke someone if all you do is sit back and nuke, but it’s easier to take out nuke defense if you build a good strike force and use it well.

It also gets you thinking about which directions nukes can come from, and which directions you could launch yours from.

Not strictly necessary, but it’d also be nice if each race had a unique second way of delivering a nuke. Each would bypass nuke defense, but be counterable by conventional units: again, more of a fight than a discrete “I clicked more times” system.

UEF build a Nuclear Bomber that must get close to its target intact to drop its payload. Anti-air can take it out quickly, and the nuke won’t detonate, so advance forces need to take out most AA defenses.

Cybran have a Walking Nuke experimental: a huge, tough block on legs with no weaponry, but which explodes with nuclear force on death. You’ll want to escort it in to give it enough protection to survive, then abandon it so your own units aren’t caught in the blast.

The Illuminate can unlock an upgrade for the Space Temple that lets them fire a nuke into it to hit the teleport destination. But the marker has to be in place for thirty seconds, and the enemy can destroy it in that time if they have the firepower. It’s a test of their base’s defenses, so if you strike while their army’s on their way to you, you’ve got a better chance of delivery.

This has always been a personal crusade of mine – I hate fog of war. It doesn’t meaningfully represent any real element of war, since regular line of sight would cover the whole battlefield on almost any map, and in any game set in modern times or later, dozens of other intel methods would give a clear picture of the scenario. But more importantly, it hurts the game in so many ways. Its crimes:

- Making the whole game look dingy and claustrophobic

- Wasting years of work on beautiful unit models by replacing them with grey squares

- Mandating endless, arduous scouting with air units – all the less welcome in a game where Air is supposed to be one of many options rather than a mandatory tool

- Robbing you of the satisfation of seeing artillery smash an enemy base. It doesn’t even compensate you with the luxury of an icon vanishing if you don’t have realtime radar coverage.

The argument in favour, as I understand it, is to let you surprise the enemy by building something he doesn’t know is coming. If that works, it reduces the game to scissor/paper/stone – complete luck. If you can see what’s being built, you have time to adapt your strategy to include a counter, and so does the enemy. To me, that’s where strategy gets interesting.

I think the tricky element can be achieved in a more explicit and localised way: each faction should have their own method of deception.

UEF can unlock a decoy engineer: everything he builds is a cheap fake that looks real to the enemy. It fits their defensive nature by making them look bigger than they are, and leads to feints like building masses of real point defense, then letting the enemy catch you building a fake one to tempt him into a doomed rush.

Cybrans have a very high-tier Land upgrade to turn the Adaptor mobile shield opaque to the enemy, so they can cluster these to conceal land units. Stealth is broken when it takes just a few hits, though, and doesn’t regenerate when the shield does.

Illuminate can Research an upgrade that makes all their experimentals appear to the enemy as regular units of a similar type, only revealing their true form and power when attacked. They already have a deceptive edge in that their Experimental factory is the same for all types of Experimental, so you can’t tell what they’re planning to build.

I also had some ideas for how a high-level campaign map could work for the single-player, and a redesign of the Illuminate to make them feel less toothless. But those are probably separate posts.

An Idea For A Better Open World Game

The last post was figuring out what we all like in open world games; this one’s about how to make that stuff work together. Can you include it all in one game, and still avoid theme-park silliness and repetitive grinding? No, probably not, but the ideas that crop up when you try are interesting. Continued

Open World Games: What Works And Why

It felt like last year open world games took over, and stopped being high-budget exceptions to the norm. It’s now pretty commonplace for a game’s linear story to be just the main attraction in a fairground of challenges, collectibles and distractions. ‘Go anywhere, do anything’ games have been around since the eighties, but it’s only in recent years developers have figured out the hooks, tricks and bribes to get a wider audience playing them.

Most of them kinda suck though, don’t they? Not the games themselves, necessarily, but their approaches to filling these sprawling open spaces with stuff to entertain you. They know how to make a traditional game, and they know how to make an open world, but their attempts to fit the two together amount to mashing a square peg into a round hole until it splinters.

I’m interested in whether there’s a way to take the most successful of these systems and make them work with the world, and each other. To fit with the fiction rather than jar with it, and to draw attention to the world rather than distract from it.

So ignoring how much we like them as games for a moment, what do some of the better open worlds fill their lands with, and how well does it work?

Assassin’s Creed 2:

- Series of story missions that lead you through each new city

- Scattered mini-missions that conform to one of a few templates (contracts, courier, etc)

- Informal missions like chasing any thieves you see

- Isolated unique puzzle/platform levels

- Collectibles, some of which assemble to shed light on the plot

The broad variety means there’s always something you feel like doing, and most of it is integrated into the fiction – albeit by clumsily grafting two different fictions together. The informal missions feel like fun because no-one tells you to do them, and failing is no big deal. The puzzle/platform levels are usually welcome because you know what you’re getting into when you take one on.

World of Warcraft:

- Miscellaneous quests

- Large scale co-op dungeons

- Resource nodes

- PvP arenas

It’s nice that there’s stuff to do wherever you go, but the lack of a main quest and presence of other players doing the same ones makes it hard to feel like what you’re doing matters.

Fallout 3:

- Series of story quests

- Character-driven sidequests without obvious rewards

- Occasional unique locations, people and loot (Oasis, Dogmeat, Alien Blaster)

The density of hand-scripted missions to find is enough that exploring is always appealing, and the unique stuff is rare enough to feel special, but common enough that everyone finds some of it. The main story has its moments, but your motivation for it is disastrously weak.

Far Cry 2:

- Two main story mission threads that sometimes merge

- Optional extra objectives to those missions with little reward

- Template mini-missions: convoys, assassinations

- A set of FedEx missions you have to keep doing to stay alive

- Trickily placed collectibles with a material reward

The main missions feel annoyingly disconnected from your objective, and the choice between them is illusory. The template missions are excellent because the templates themselves are compelling, but they never feel like more than that. The thoughtful placement of collectibles makes them much more fun to hunt, even if you don’t need the money.

Prototype:

- Series of story missions that change the city from peaceful to wartorn

- Fairground-style challenges

- Collectibles and destroyables that grant XP

The story missions are mostly bad, and the challenges are ridiculously divorced from the fiction. The changing city would be cool if you could make any of it yours, but instead the only influence you have is deciding which of two factions that hate you control certain bits.

Red Faction Guerilla:

- Series of story missions that conquer each area, making it safe and unlocking new one

- Template mini-missions: hostage rescues, defenses

- Fairground style challenges

The mini-missions do a good job of providing a choice of fun stuff to do without breaking fiction. The fact that the story moves on from each area, though, makes it feel less like a world and more like levels.

Just Cause:

- Series of story missions

- Scattered identical mini-missions to take over settlements

- Template mini-missions

- Collectibles

Since the mini-missions keep you in a small area and are very similar to play, they don’t offer much of a break. Neither do they or the collectibles carry an appealing reward.

It seems like the things that work best, or are most needed, are:

- Informal missions – opportunities you spot rather than jobs you’re ordered to do

- Collectibles that improve you, in places it’s fun to visit

- Categorised missions, so you can choose what kind of job you want to take on next

- Scraps of story scattered about to make your adventure feel meaningful

- Unique things you can find, take and use

- The ability to change or add to some part of the world

- Variety – at every stage you should have more than two meaningfully different options for fun things to do next

Any additions? Anything you really like in open world games in general, or a specific one? The next post will be figuring out how to cram all the good stuff into one specific open world.

What’s Wrong With Team Fortress 2’s Unlocks

I cooed a little about the amount of free stuff Valve have added to TF2 since release, but it’s not purely to fix or improve the classes. They’ve been experimenting with ways to leverage this free content to add an element of persistent progress and character customisation to TF2. But their experiments have been weird, and so far the resulting system doesn’t really do its job. If you’re all too familiar with why the current system needs changing, you can just skip to how I suggest changing it. Here’s what’s wrong:

You can unlock weapons for a class by earning its achievements. That means everyone plays the same class when its new weapons are released, even before they’ve earned any of them. We’re bribed to play that class at the very time when TF2’s primary problem is inevitably going to be too many people playing that class. And we’re often bribed to play it in counter-productive ways to fulfill achievement criteria, some of which are just fun little jokes.

You can ‘find’ weapons and hats randomly. On the plus side, that sometimes gives you a weapon for a class you don’t normally play, encouraging you to try it out. On the down side, well:

- A lot of what you find is duplicates of what you already have, which means that little gold message comes to be associated more with disappointment and absurdity than excitement or pleasure.

- People’s fortunes vary wildly without any correlation to skill. Some people play for hours a night, rarely get a weapon, find only dupes, and have never seen a hat in hundreds of hours of play. Others consistently get unlocks every half hour or so, and have copious hats for classes they don’t even play.

- Consequently, very rare and exclusive class items like hats don’t signify anything when you see a player wearing them. What does the mighty Camera Beard tell you about a Spy? Nothing, he just got lucky.

You can ‘craft’ items by combining lots you have to produce one you might not. Presumably meant to tackle the dupes problem with the random drops, but what we understand of the current system is totally bizarre. If you don’t have the Eyelander, you seem to need six copies of the other two Demoman weapons, plus at least eight melee weapons, to craft one without losing anything you need. In a given time period, you’re about 13.8 billion times more likely to just find an Eyelander than what you need to make one.

For a hat, you’d have to find eighty-one weapons you don’t need just to make a random one. To have more than a 3.4% chance of crafting the one you want, it takes a hundred and twelve. At the end of which, you’ve got something a new player might find in his first hour with the game.

That’s what’s wrong with the current system. I think it needs a few changes to work as an addictive RPG, as a way of customising your characters to your tastes, and as a way of showing off your skill or dedication in the way you dress. The unlocks system ought to make the repetitive violence feel like part of a larger goal, and give you a sense of progress even if you lose. Here’s how I’d do it:

Unlockable Weapons: You’d be able to browse these from the main menu to see what’s available, and select one you want to unlock. Each requires somewhere between 250 and 500 points, and once you select it all the points you score in-game, as any class, count towards that. That’s about 2-4 hours play – the Flare Gun might be 250, the Direct Hit 500. You need to be in a game with at least four non-idle players or bots for your points to count, but beyond that anti-exploit measures are probably futile.

On top of that, every five hours or so you’ll get a random weapon unlock that you don’t already have. If it’s the one you’re working towards, points earned so far transfer to what you pick next.

The idea: Every match gets you closer to something you really want, and the items you choose first make you a different player to those around you. At the same time, you can still get something unexpected for a class you don’t normally play that might encourage you to try them.

Achievements: I think they should stay – I even think the silly ones should stay. In fact, I’d get rid of the sensible ones, and just leave the ridiculous accomplishments – taunt kills, ironic deaths, corpse dancing and tortured puns (Slammy Slayvis Woundya? That’s what you’re going with?). But they no longer earn you weapons, they’re just an acknowledgement for any time you do something remarkable.

The idea: Silliness absolutely has a place in TF2, and trying to get things like taunt kill achievements just makes the game hilarious for you and your enemies. But no-one should be bribed to go for them if they don’t want to.

Feats: This is where the sensible achievements would go. They’re things that genuinely benefit your team, so you’re rewarded each time you do them: some bonus points towards your unlock (but not your in-game score) and a little pop-up: “Medic Feat! Extinguished five team-mates, +2 points”. Things like multi-kills, capturing a point alone, setting light to a cloaked Spy, killing a fully charged Medic, or making the winning capture would always be rewarded.

The idea: By letting people know they’ll be rewarded every time they do this, it both teaches and incentivises intelligent play. Achievements already do this a little, but not reliably: plenty of the actions they suggest are actually pretty dumb.

Unlockable Hats: These are handled separately, but again you choose which you want to unlock. When you do, only points and feats earned as that specific class count towards it, and the number required is in the thousands – twenty hours’ play for most, more for some special prestige items. You still earn points towards your weapon unlock at the same time.

The idea: A hat says “I play this class, I play it well and I play it a lot”. A Camera Beard says “I am amazing or crazy.”

Crafting: No crafting. I don’t think the system is entirely unsalvagable, and Chris Livingston does a good job of salvaging it in a much shorter post than mine. But ultimately any full crafting system hinges on finding dupes, which I think ruins the “ooh, I found something!” moment by diluting it with disappointment.

A Different Way To Level Up

Levelling up is pretty much the heart of RPGs, because it does these cool things:

- Makes you feel like you’re achieving something by playing.

- Gives you new abilities to try at well-paced intervals.

- Lets you enjoy feeling more powerful than you used to be.

All this makes repetitive tasks feel worthwhile and even fun, which is particularly useful in a massively multiplayer game, because you don’t want players to get through all your content quickly, get bored and stop paying you a monthly fee. Continued

![[FBP] Dirty Squirrel is looking good!_0002](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4052/4207772952_4a98696b4d.jpg)